The Future of Work: Balancing AI Innovation with Humanity

Micah Kessel

on

January 14, 2025

As artificial intelligence (AI) continues to reshape the professional landscape, we find ourselves grappling with a pressing question: How can humanity preserve its essence and empathy in a world increasingly dominated by machine intelligence?

At the recent ‘Work in Progress’ conference, we came together as a diverse group of investors, organizational leaders, futurists, and corporate coaches to explore this challenge. Spanning a 20-year age range and representing experiences across three continents, we shared a collective familiarity with the U.S. professional environment, which grounded our discussion in a shared context.

Our task in this working group was to redefine the roles of leaders, managers, and individual contributors in workplaces increasingly influenced by AI. As our conversations deepened, an additional goal emerged: to imagine what these roles might look like in a more distant, AI-integrated future.

To anchor this exploration, we first established several foundational truths:

- Acknowledging Humanity’s Current Role

To imagine humanity’s place in an AI-driven world, we first needed to reflect on its presence—or absence—in the workplace over the past three decades and today. - Recognizing Literacy as a Double-Edged Sword

We noted that 100 years ago, the global population was 2 billion, with a literacy rate of just 15%. Today, with nearly 7 billion people, literacy has risen to 85%. While education is a gateway to freedom, its potential to foster a more humane workplace depends on its ability to equip individuals with usable skills and nurture cultural flourishing. - Balancing AI’s Promises and Threats

AI presents both opportunities and risks. It can amplify educational access and workplace productivity, but it also challenges humanity’s role in fostering empathy, creativity, and cultural connectivity. - Examining the Human Condition at Work

With significant investments in learning and development (L&D), talent development, and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), we considered key elements that enhance or hinder individuals’ ability to learn and thrive in the workplace. These elements were categorized into seven dimensions:

- Time: The availability or scarcity of it.

- Agency: Individuals’ ability to influence outcomes.

- Fulfillment: A sense of purpose and satisfaction.

- Safety: Specifically, psychological safety.

- Equality of Wellness: Access to resources that ensure well-being.

- Visibility: The ability to be seen and heard authentically.

- Elimination of Threats: Reducing barriers and hostilities.

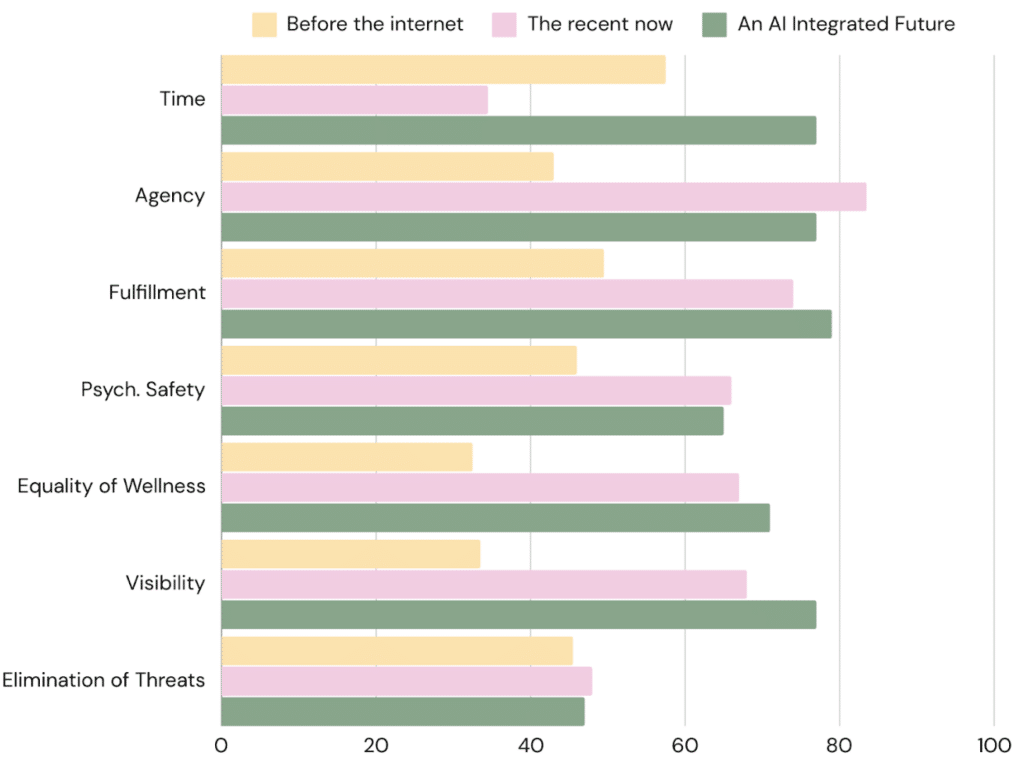

Each participant rated humanity’s progress across these dimensions in three periods: before the internet, in 2024, and in a speculative future. This data, informed by the insights of ten diverse workplace experts, provides a nuanced view of how workplace experiences might evolve across three pivotal eras: “Before the Internet,” “The Recent Now,” and “An AI-Integrated Future.” Rather than offering definitive conclusions, these findings illuminate potential trajectories and areas of focus as we navigate an increasingly technology-driven landscape.

Empowerment and Fulfillment

For these workplace experts, the perception of agency appears to have risen dramatically, moving from 43 in “Before the Internet” to 84 in “The Recent Now.” This rise suggests an increasing focus on individual autonomy and purpose in the workplace. However, the slight decline projected in the AI-integrated future (77) hints at lingering uncertainty around balancing human autonomy with technological intervention.

The pre-Internet workplace was described with words like “transactional,” “command + control,” “punch the clock,” “dehumanizing,” and “a lack of individual purpose.” These words paint a picture of a rigid and authoritative environment where work was often seen as a means to an end, marked by linear, serial processes and a lack of personal fulfillment.

In contrast, fulfillment shows a steady rise over time, peaking at 79 in the AI future. This suggests the possibility of work increasingly aligning with individuals’ aspirations and values, aided by systems designed to enhance meaningful engagement. The AI-integrated future is imagined as a period of “empowered potential,” “creativity,” “personal agency,” and “a world beyond scarcity.” Experts envision workplaces where humans have the “time and tools to be their fuller creative selves” and find fulfillment in a “harmonized” and “adaptive” environment.

Equality and Visibility as Emerging Priorities

The data suggests a notable upward trend in Equality of Wellness and Visibility, with both metrics growing substantially from their pre-Internet baselines (33 and 34, respectively) to over 70 in the AI future. This may point to a growing recognition of fairness, inclusivity, and transparency as critical drivers of healthier and more equitable workplaces.

The pre-Internet era’s emphasis on “static knowledge written by homogenous experts” and “binary, authoritative systems” contrasts sharply with the “searching for creative alignment,” “greater autonomy,” and “remembering humanity” that characterize the recent now. Yet, challenges such as “unequal access,” “overload,” and “generational differences” remind us that progress remains uneven.

In the AI future, experts envision workplaces marked by “decentralized ownership,” “greater purpose beyond work,” and “humanized systems.” Such changes imply the potential for workplaces to transcend structural inequalities and focus on cultivating “flexibility, choice, and impactful contributions.”

Challenges in Psychological Safety and Threat Mitigation

While Psychological Safety has grown from “Before the Internet” (46) to “The Recent Now” (66), its projected stabilization at 65 in the AI future suggests potential barriers to further improvement. This may reflect the complexities of fostering emotional well-being in increasingly digitized and augmented environments.

The pre-Internet workplace, described as “authoritative and firm” with a “lack of individual purpose,” offered limited support for psychological safety. The recent now, while more “collaborative” and “flexible,” also carries challenges such as “frustration,” “burnout,” and “overwhelmed information flows.”

The AI-integrated future, imagined as “peaceful,” “constant learning opportunities,” and “adaptive,” offers the possibility of greater psychological support but also raises questions about the human-technology dynamic.

Meanwhile, the Elimination of Threats metric remains relatively unchanged across the three periods (46, 48, 47). This suggests enduring challenges in addressing perceived or systemic risks, even as workplaces evolve.

A Changing Relationship with Time

The perception of Time undergoes a profound shift, with the metric rising from 58 in “Before the Internet” to 77 in the AI-integrated future. This evolution reflects how technology might transform notions of productivity and work-life integration.

In the pre-Internet era, time was often “linear,” “serial,” and “analog,” reinforcing rigid and dehumanizing structures. By “The Recent Now,” the group describes a world that is “constantly connected,” “digitized,” and “global,” yet often leaves individuals feeling “overwhelmed” and “burned out.”

The AI future is imagined as a time when workplaces enable “more time and less work,” fostering “seamless experiences” and providing individuals the space to “harvest creativity” and pursue “greater purpose beyond work.”

A Vision for the AI-Integrated Workplace

These expert perspectives highlight possibilities for an AI-driven future. While advancements in agency, fulfillment, equality, and visibility suggest a promising trajectory, the plateauing of psychological safety and stagnation in threat elimination underscore areas requiring intentional focus.

Rather than presenting a utopian vision, these insights invite reflection on the nuanced interplay between technological progress and human well-being. As workplaces evolve, leaders are encouraged to design systems that enhance not only productivity and fairness but also intangible elements like trust, safety, and emotional resilience.

Tomorrow’s Roles: Preparing Leadership and Teams for an AI-Integrated Future

As workplaces evolve toward an AI-integrated future, the roles of leaders at every level must adapt to meet the demands of this new era. The insights from workplace experts suggest a future where decentralization, creativity, equity, and human empowerment become central pillars of success. For C-Suite executives, venture capitalists (VCs), and board members, this means redefining their responsibilities to align with emerging priorities like psychological safety, adaptability, and the seamless integration of human and AI capabilities.

The following outlines essential additions to their job descriptions, ensuring leadership not only navigates but thrives in this transformative future and that managers and teams can play their harmonious role herein. These changes reflect the need for a more human-centric approach, balancing technological innovation with purpose, inclusivity, and well-being.

Additions to Job Descriptions for C-Suite Executives, VCs, and Board Members in an AI-Integrated Future

For the C-Suite

- CEO (Chief Executive Officer)

- Champion decentralized decision-making and empower cross-functional collaboration between human and AI teams.

- Foster a culture of continual learning, adaptability, and creativity within the organization.

- Lead efforts to align corporate vision with broader societal goals, such as equity, sustainability, and well-being.

- Ensure transparency in AI implementation and its alignment with ethical standards.

- CFO (Chief Financial Officer)

- Integrate long-term, purpose-driven metrics into financial planning, focusing on sustainability, equity, and impact.

- Leverage AI to optimize resource allocation while considering human energy and well-being.

- Analyze the financial implications of transitioning to more flexible work structures, such as reduced hours or creative sabbaticals.

- COO (Chief Operating Officer)

- Orchestrate adaptive workflows where human and robotic agents collaborate seamlessly.

- Ensure operational strategies prioritize psychological safety, inclusion, and fulfillment.

- Implement systems to measure and enhance team member alignment with organizational purpose.

- CHRO (Chief Human Resources Officer)

- Prioritize emotional intelligence and psychological safety as key components of leadership development.

- Develop programs to support human creativity, flexibility, and well-being, leveraging AI for personalized career pathways.

- Address systemic inequities by implementing tools and policies that create a level playing field for all employees.

- CMO (Chief Marketing Officer)

- Emphasize the integration of storytelling and humanized branding in AI-driven campaigns.

- Advocate for transparency in AI usage to build trust with consumers and stakeholders.

- Focus on aligning brand identity with societal values, emphasizing empowerment, purpose, and inclusivity.

- CIO/CTO (Chief Information/Technology Officer)

- Lead ethical AI innovation, ensuring systems augment human potential rather than replace it.

- Design technology systems to support decentralized ownership and adaptive collaboration.

- Monitor AI systems for unintended biases and align their outputs with organizational values.

For Venture Capitalists (VCs)

- Evaluate startups based on their ability to harmonize AI advancements with human empowerment and societal impact.

- Advocate for funding models that prioritize creativity, well-being, and sustainability over pure scalability.

- Mentor founders on the importance of psychological safety and equitable practices in building resilient organizations.

For Board Members

- Ensure strategic oversight prioritizes long-term societal impact alongside shareholder returns.

- Act as stewards of ethical AI deployment, holding organizations accountable for transparency and fairness.

- Provide governance that supports flexibility and creativity in the workforce, aligning with evolving values of the AI era.

- Promote alignment between organizational purpose and global challenges, encouraging a higher purpose beyond profit.

For Managers

- Enable Purpose-Driven Work: Act as a guide to help individuals align their roles with their personal aspirations and the broader organizational mission.

- Promote Collaborative Leadership: Shift from directive management to coaching and facilitation, empowering teams to co-create solutions in collaboration with AI systems.

- Leverage AI for Personalized Support: Use AI to identify team members’ needs, skill gaps, and career development opportunities, offering tailored growth pathways.

- Balance Workload and Well-Being: Advocate for flexible schedules, creative sabbaticals, and AI-enabled efficiencies to help reduce burnout and enhance fulfillment.

For Individual Contributors

- Embrace Lifelong Learning: Commit to continual skill development, especially in areas where human creativity, emotional intelligence, and decision-making complement AI capabilities.

- Cultivate Creativity and Innovation: Harness AI tools to unlock new ways of thinking, problem-solving, and generating impactful ideas.

- Adapt to Hybrid Collaboration: Learn to work seamlessly with AI agents, understanding their capabilities and leveraging them to enhance productivity and outcomes.

- Prioritize Purpose and Impact: Seek roles and projects that align with personal values, leveraging AI to achieve greater meaning and influence in your work.

- Advocate for Equity and Inclusion: Actively contribute to creating an environment that is fair, inclusive, and supportive of diverse perspectives and talents.

Far Beyond Tomorrow: Futurist Roles for a Changing World

A recurring theme in the conversation was the evolution of leadership models. One participant proposed moving away from rigid hierarchies:

“What if leadership itself shifts from this hierarchical structure into this infinity model of leadership where things are done, and the person who’s leading does it based on whoever has the most expertise in that area?”

This vision of leadership emphasizes adaptability, with leaders transitioning fluidly between roles to support collective expertise. Such a system could foster collaboration and inclusivity while dismantling traditional power dynamics.

The rapid pace of technological change demands new professional roles to address emerging needs. Suggestions included:

- Regeneration Specialists: Focused on reciprocity, ensuring organizations give back to the ecosystems and communities they impact.

- Nervous System Regulators: Addressing the overwhelm caused by constant change and fostering holistic well-being in business.

- Chief Potential Officers: Helping individuals and organizations embrace their full creative potential by moving past scarcity-driven mindsets.

“We’re going to need to help people shake off the way we’ve always worked and move into our full creative selves,” one contributor emphasized.

The Role of Research and Real-Time Analysis

In a rapidly shifting environment, research and analysis will play a pivotal role in interpreting trends and mitigating risks. As one participant noted:

“There’s going to be a lot of trial and error, and researchers need to make sense of what’s happening. Real-time analysis becomes something totally different.”

To remain effective, these roles must bridge the gap between idealistic visions and actionable insights, ensuring that data-driven decisions align with both ethical principles and practical business needs.

Ethical Guardrails and Global Collaboration

As AI becomes increasingly integrated into decision-making, the potential for dehumanization is a concern. One participant posed the critical question:

“Who is advocating for humans? Who’s going to stem the tide from an integration that destroys the human element?”

This led to discussions about roles like a “Protector of Humans,” tasked with safeguarding human dignity, ethical considerations, and societal balance. Another participant added, “Do we program AI to protect humans at all costs?”

The ethical challenges posed by AI development cannot be overstated. As one participant put it:

“Just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should. And even if we should, it doesn’t mean we should do it right now.”

Discussions highlighted the need for international standards and ethical governance to guide AI’s evolution responsibly. However, nationalism and competing interests may hinder such collaborative efforts.

Education and Creativity as Cornerstones

A shift toward a more human-centered future also requires rethinking education. A participant suggested:

“We need educators who can help bridge the gap between technological advancements and human understanding. Designers of education will be critical.”

This aligns with the call to nurture human creativity, distinguishing authentic human expression from synthetic creations.

Conclusion: A Protopian Vision

Amid the challenges, there’s a hopeful vision of a “protopian” future—a world where progress is incremental and grounded in reciprocity and shared humanity. As one participant concluded:

“For organizations to thrive, they must evolve to play a role in the kindness and regeneration of resources, shaping a society rooted in compassion.”

The future of work is not just about adapting to AI but about redefining what it means to be human in an interconnected, technologically advanced world. By fostering ethical leadership, embracing new roles, and prioritizing human creativity, we can navigate this transformation with purpose and resilience.