Lowering Screen Fatigue by Connecting Meaningfully Online

Why you should call your friend, even if you don’t feeeeeeel like it.

Why you should call your friend, even if you don’t feeeeeeel like it.

A theoretically revolutionary take on how to approach organizational DEI, called ‘Two In The Room’

We are at a time of history when we are told that to move forward, we must bring the two most extreme edges together, pulling them towards the middle through dialogue.

That when dialogue meets in the middle, and the ends of the political spectrum listen to each other, depolarization will occur.

In reality, we haven’t seen that happen. In fact, we see it only polarizes us further.

But what about the middle that already exists? Those who, in their hearts, want inclusion and belonging for all. They just don’t know how to make it happen.

Our diversity, equity, and inclusion leaders have done everything they could to give the middle that knowledge, through facts, statistics, and exercises.

But when we asked more than 100 DEI directors in organizations across the country what their biggest challenge is, we consistently hear that after all of those trainings, they’re not seeing people apply that knowledge in their teams and communities.

And so by looking at our nation’s complicated strategy in defeating racism, speaking with the brightest researchers on bias, and the science of emotions, we came up with a clear starting point for change. This starting point is actionable, can change lives, and can be represented in one powerful easy to remember phrase:

TWO IN THE ROOM. Specifically, two people in every room who are comfortable and willing to speak up for the rights of others.

Two in the Room is the basis for our theory of change — we can make radical change without needing to change the radicals.

We live in a world of teams — our community groups, our families, our classrooms. Our corporations and organizations are made up of teams. We may think we know what makes a team great. But do we?

Google wondered the same thing. In 2015, the company conducted a study of their 150 teams known as “Project Aristotle.” Rather than similar educational backgrounds or interests, or the perfect blend of introverts and extroverts, it was the rituals and unspoken rules that bonded the team members hold valuable, i.e. “how the team worked together.” Google’s research revealed that the most important element of a successful team was psychological safety. As defined by Harvard Business School Professor Amy C. Edmondson in her book The Fearless Organization, psychological safety is “a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes.” Team members can have ideas and take the risks that often lead to innovation, and do so while staying part of the whole.

That foundation of psychological safety leads to healthy dependability and a sense of purpose and self-determination, the clarity necessary to achieve key point indicators, a sense of purpose, higher job satisfaction, employee retention, higher boosts in productivity and revenue.

Here’s the catch: We do not believe that you can have a psychologically safe team that does not feel inclusive. You’ve likely already experienced this: You’re in a planning meeting with colleagues, and someone on the team makes a sexist comment. If this is met with awkward silence, sharing ideas becomes less comfortable. If someone tries to manage the conversation because you’re out of time, people will start showing up less consistently. If someone sides with everyone because they think that it’s empathetic to avoid conflict — because they lack the point of view to see how a sexist comment reflects the systemic bias embedded in our organizational cultures — this will also destroy psychological safety. Without inclusivity, the loss of psychological safety results in the loss of dependability, impact, and ultimately, success.

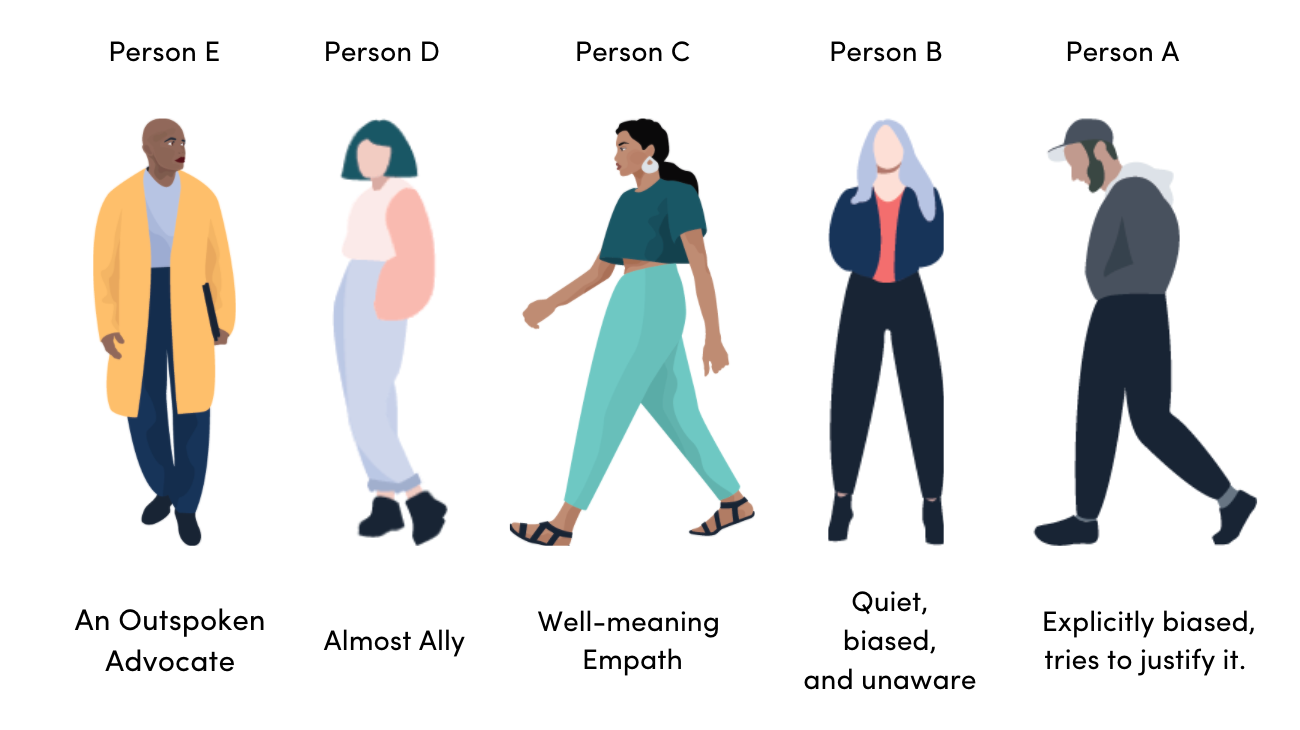

We are not a country of binaries, such as racists and non-racist, sexists and non-sexist. Instead, we’re all somewhere on a spectrum of bias about particular issues and identities. At one end of the spectrum are the advocates, already outspoken against bias. At the other end, there are explicitly biased people who think the world is a meritocracy, and say everyone has a fair chance it’s just about what you put into it. In the very large middle, there are three groups:

Imagine that each of these groups are represented by five people in a room at work, and perhaps you’re one of them. Our tendency is to focus energy and attention on Person A, “The Problem,” because they can create the most outrage, as well as the most paperwork for human resources departments. Because implicit bias is both historical and environmental, the chances of moving Person A towards the inclusive end of the spectrum is difficult. A 2019 study published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that “residents of counties more dependent on slave labor in 1860 display greater implicit bias measured up to 156 years later.”

Bias can be viewed as a wave in a football stadium. If a section of the stadium across from you begins the wave, it’s more likely that you’ll stand up if those around you stand up as well. Implicit bias is much the same, according to Heidi A. Vuletich (Indiana University Bloomington) and B. Keith Payne (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill): “Implicit bias is a social phenomenon that passes through individuals like ‘the wave’ passes through fans in a stadium. Rather than a property of individuals, it may more properly be considered a property of social contexts.”

Then, what do we do next? We look all the way to the left, and say ‘help us solve our problem’ to the DEI groups, and to the ERG’s. Now we’re all aware of the problematic nature of asking the most victimized and marginalized to solve an organization’s problem.

In a study of nearly 600 finalists for university teaching positions, if there was only one woman in the candidate pool, she had no chance of being hired. If there were two or more women in the candidate pool, “the status quo changed, resulting in a woman…becoming the favored candidate.”. Being the only woman in a pool of finalists highlights how different she is from the norm, which makes hiring her a risky choice.

Likewise, when Person E speaks up, it highlights a deviation from the status quo. It takes that second person in the room — Person D — speaking up as well, thereby making Person E’s viewpoint more viable, and shifting the environment. Because bias is environmental, Person C may not yet be ready to speak up, but will want to learn the tools to address his/her biases. As the environment shifts further, Person B may start to recognize his/her biases, and Person A may become less vocal. By helping those in the middle of the spectrum walk in the shoes of others and gain the exposure to apply their knowledge, Person B will become Person C, Person C will become Person D, and even Person A may change their viewpoints because they realize their environment no longer finds it acceptable.

How do we find those almost allies — those second people in every room — wanting to become advocates?

Well, on one hand, we know who they are, because many of them have stepped up and said, we want to do more for Black Lives Matter. Many have gone to their ERG’s or their marginalized peers and again, said, ‘tell me what to do to not be racist, sexist, gender non-affirming, ableist, and so on. And so the good news is, the second person is making themselves more visible.

If they are less visible that 20% percent of your organization, not including outspoken advocates, then notice who shows up for voluntary trainings, workshops, or discussions involving race, gender, or sexual orientation.

But this survey shows us how this second person in the room is making up a very significant 1/5th of our organizations, and is not being activated to support DEI efforts effectively.. In this study, Payscale asked 27,000 people in the workforce, two questions. The first question was, in most workplaces, do men and women have equal opportunities? Yes I agree, or no I strongly disagree. The second question was in my workplace, do men and women have equal opportunities?

One in five said, NO, women do not have equal opportunities in most workplaces and NO, also not where I work. These people get it. They get that bias exists, and they also see it environmentally, and are likely the first person in the room, already an outspoken advocate. Three in five people said, Yeah, women have equal opportunities in most workplaces, and YES, also where I work. These people don’t get it. They don’t necessarily even feel or understand the bias existing on national level, and so they’re harder and much more effort to help directly.

The final one in five said, NO, women do not have equal opportunities in most workplaces. But YES, they DO have equal opportunities here, where I work. These folks understand that bias exists; they get the concept, but they lack the point of view to see it environmentally.

But if we can get this second in five to see locally, what they believe nationally, and stand next to the advocate. Then at the next planning meeting, a sexist comment will be met with someone speaking up to say, “I found that remark to be sexist.” Rather than try to manage the conversation, the second person in the room will jump in with, “You know, that bothered me as well. With the few minutes we have left, let’s talk about it as a team.”

That is a team that actually builds their safety and belonging. And a country of teams creating two in the room, comfortable and willing to speak up for the rights of others bends the moral arc of our professional environments.

Seven steps to revolutionizing your viewpoint on DEI:

1.) Acknowledge that your success is based on a foundation of psychological safety within your teams.

2.) Realize that psychological safety depends on inclusivity.

3.) Your teams are on a spectrum. We’re all aware of the outspoken advocates and the explicit racists, but within the middle, there are the “almost allies,” vital to really moving the culture to be inclusive, yet very difficult to identify. This is because they are hungry to help and armed with facts and information, but are missing the exposure to difference to apply their knowledge. The get it conceptually, but not emotionally, so the culture doesn’t shift.

4.) If this is the group that will shift the middle, and shifting the middle will shift the culture, then we need to stop focusing on the explicitly biased people because they have history and environment working against them and are an inefficient use of our efforts. Since environment is a major determinant of bias, they will shift more easily once the middle shifts.

5.) Shifting the middle — and thereby shifting the moral arc of the environment — is all about that almost ally: the second person in the room. The second person in the room understands that bias exists, but lacks the point of view to see it in their own environment.

6.) Getting the second person in the room to become comfortable and willing to speak up for the rights of others is like tapping a finger in the middle of a still lake, and causing a ripple effect that will create ongoing waves of real measurable impact.

7.) Almost allies already think about bias. They need to feel and personalize bias to shift.

By having these almost allies walk in the shoes of others, we give them the emotional catalysts and exposure to people who are different than them.

You will create the missing link between their motivation to support marginalized groups and the relatability to marginalized groups necessary to really stand up for them. You will create two people in every room, comfortable and willing to speak up for the rights of others, which will soon become, three of five, four of five, and eventually, your whole organization. Two in the room is what you need to be investing in, catalyzing, and measuring.

And that is how you create radical change.

Edited by Deb Fiscella, May 2021

An article written for executives, managers, and ERGs to engage in empathic, positive, and fruitful progress.

There is a huge invisible challenge facing DEI today. That challenge may best be described as Inclusion vs. the Ticking Clock

We know from over 300 one-on-one conversations with DEI directors all over the country that while teams are learning the facts of DEI, they’re not applying the knowledge to create an inclusive environment. What accounts for this?

Attached to this question is a huge Ticking Clock: We need to act sooner than we might think. To quote the poet Prageeta Sharma:

“Americans have an expiration date on race the way they do for grief. At some point, they expect you to get over it.”

As an industry, we’ve been signaling to our teams that improvements in organizational diversity and equity can make up for a lack of improvement in inclusion. In order to take advantage of the momentum of the last two years, leaders need to own up to this. We’re using the word “strategy” to kick the problem down the road. It’s time we picked it up before the country stops paying attention.

Every week, I talk with multiple chief diversity officers (CDOs) at Fortune 500 companies. Recently, I was speaking with a savvy and diligent executive who summed up the above-mentioned problem brilliantly.

She had spent the last few months making phone calls to CDOs at other major organizations, asking how they were measuring inclusion – and coming up short with every phone call. The answer again and again was: “we don’t know how.” This echoed what I’ve been hearing from nearly all of the 300 leaders in DEI I’ve spoken with nationwide.

According to a Harvard Business Review article from 2012, current DEI training and outcome measurements fail to consider the factors required to create a truly diverse workplace.

The article states: “A study of 829 companies over 31 years showed that diversity training had ‘no positive effects in the average workplace.’ Millions of dollars a year were spent on the training resulting in, well, nothing. Attitudes — and the diversity of the organizations — remained the same.”

Not much has changed since then.

Even in laboratory environments where DEI interventions are conducted as carefully as possible, a recent meta-analysis reviewing 418 such experiments concluded that “much research effort is theoretically and empirically ill-suited to provide actionable, evidence-based recommendations for reducing prejudice.”

The methods we’ve been relying on simply aren’t working in practice.

Since the conversation around diversity outcomes is mostly taking place within businesses and organizations, DEI professionals are creating policies aimed at producing key performance indicators (KPIs) that they can show to the leadership. Typically, this looks like metrics around the number of diverse hires or how effectively the pay gap is closing.

Unfortunately, these data points simply aren’t sufficient.

They don’t speak to the underlying emotions at the core of a diverse workforce: a sense of belonging, willingness to collaborate, or how likely an employee is to stay at the company. As such, inclusion is not moving forward because DEI, as an industry, lacks the ability to generate and communicate the results of its programs in terms of inclusion and belonging.

This issue is not insurmountable, especially when you consider that dozens of tools exist to measure emotional interconnectedness. So what is the roadblock? Why are we having trouble keeping pace?

Some organizations simply don’t have the bandwidth for anything more than checking the boxes of legal policies and hiring practices. The more nuanced elements of inclusion seem too difficult to apply to the business, so they retreat to more measurable outcomes, such as more diverse teams or reductions in the pay gap.

The problem is, these metrics don’t reflect the reality of those in the workforce.

After Dr. Timnit Gebru’s termination from Google, employees described, in their letter to management, how more diverse hiring cannot erase the discomfort of feeling like they do not belong. Similarly, while efforts to close the pay gap are a positive step forward, if someone feels ostracized from their peers, they won’t be happy or successful in that environment.

As James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, notes:

“just because you can measure something doesn’t mean it’s the most important thing. And just because you can’t measure something doesn’t mean it’s not important at all.”

There is a lack of understanding around the ability to quantify “softer” measurables, such as empathy and emotions. The DEI community is in a position to tell their organizations that it is quite possible to measure inclusion – they just might not know how to yet.

This missing understanding stems from a lack of interdisciplinary collaboration between DEI strategists and social scientists (eg. neuroscientists and psychologists) who measure emotions and empathy. This collaboration requires investments in academic consultants that go beyond two or three sessions. I would argue that for every three DEI hires in a company, there ought to be one social science position created to support HR and DEI consultants in measuring inclusive mindsets. It’s what many social scientists have dedicated their lives to.

At Empathable, we’ve found that one of the most vital elements of our engagements is the application of an empathy-based measurement framework. This is because empathy is highly learnable – much more than we think. As empathy researcher Jamil Zaki emphasizes, empathy is a muscle that we learn to train, not a skill we’re born with. That means it helps to:

When considering how to quantify changes in empathy, the challenge isn’t finding a system of measurements. It’s having knowledgeable experts who can help you choose and apply the right measurements for a given context. For example, there are many different questionnaire frameworks to measure empathy. According to the Stanford School of Philosophy, these questionnaires highlight various forms of empathy and how it’s understood. The popular Hogan questionnaire focuses on mentally understanding someone else’s emotions:

With the right minds at the table, such measures could be applied to reimagine the content, frequency, and measurements involved in DEI training. Ultimately, over time, this would lead to an improvement in team performance.

In a DEI context, where progress and buy-in can feel nearly impossible, tools like this become all the more important. Tying these inclusion measures to business outcomes is the next step, and we’re working on this vigorously.

It’s clear to us that this outcome is possible, and the Ticking Clock confirms its urgency.

When we deepen the sense of belonging in a group, employees will be inclined to stay at an organization longer. According to research from the University of British Columbia, people who report feeling isolated from their workplace show a stronger intention to quit and lower commitment to the job. By improving a sense of belonging, there will be concrete, visible progress in diversity and equity, and the subsequent organizational improvement in not only retention but also revenue.

At Empathable, our team uses psychology, neuroscience, and the outer limits of artistic design to create interactive spaces within which to learn. These experiences are designed to promote empathy across perceived “differences,” including socially-constructed divisions such as gender, race, and age. The immersive process helps participants to contextualize their inner biases to the people around them, which increases inclusion.

Schedule a Demo to learn how to invite empathy into your organization.

—

Special thanks to Anushri Kumar, Savannah Johnson, Deb Fiscella, and David Kessel for their support in writing this article.