Why Your Most Caring Leaders Struggle to Scale Their Empathy

Micah Kessel

on

May 23, 2025

Most organizations, in the face of two managers with similar competencies, will naturally promote their most empathetic—those who excel at building trust, not only understanding individual needs but also embracing different perspectives and creating psychological safety within small teams. But when teams expand, the very skills that made them successful with 10-15 people often fail them when they’re suddenly responsible for 50, 80, or hundreds of employees. According to HBR, in 2023, 70% of newly promoted managers struggle with the transition from managing individuals to managing systems. Whether organizations realize it or not, this reveals a gap in operationalizing empathy, and with never-ending restructuring for strategic and financial considerations, those who do not receive direct care from their manager often fall to the wayside, losing their sense of purpose, engagement, and ultimately performing less well.

Better companies teach managers to be better listeners and emphasize the importance of psychological safety and taking different perspectives into consideration when helping a team move forward, but they don’t show them how to build that at scale. This is why many individual contributors lose a sense of their considerations being taken seriously and therewith, lose a sense of meaning. That’s sad considering there are effective ways to show you care about a group of people without a lot of personal time and it’s exactly that that helps ever-changing teams move forward together.

As you may know by now, at Empathable, we believe leaders learn better when we go beyond teaching them concepts – but rather, through real stories from real professionals. So instead of presenting a traditional analysis and set of approaches, I’ll take you through a real story from someone who I’m calling Akira Johns to respect their privacy. This story illustrates how one can scale individual empathetic talents to larger teams where you don’t necessarily have direct impact.

When Everything Changes

Imagine Akira Johns, a burgeoning manager at a Fortune 1000 who thought she liked her job, staring at her computer screen this morning, processing the announcement that: ‘due to company restructuring post acquisition, her team of 15 direct reports was about to become 80 people across three departments.’

Akira had built her reputation on being a thoughtful leader—knowing each team member personally, remembering their challenges, and ensuring everyone felt heard in meetings. But 80 people? How could she make the time to maintain those meaningful connections? She’d need three of herself. How would she know when someone was struggling? How could she gather diverse perspectives when she couldn’t possibly meet with everyone regularly? How would she keep everyone engaged?

Somewhat hopefully, she saw the next message in her inbox, which was from Akira’s beloved learning and development director who pinged her to let her know that with these big changes, she’d been selected to be part of a cohort of 100 burgeoning managers would be working with Empathable, an organization that specializes in scaling the weaving of empathy into essential leadership skills—starting with a facilitated kickoff, then a light-touch deep immersion learning experience. Once every two weeks for the next six months, Akira would join cohorts with four other managers to walk in the shoes of other seasoned managers coupled with best in class expert perspectives. People who had already considered deeply how to take into account all aspects of scaling empathy, taking no more than one hour of their time per month.

But this hour wasn’t filled with random perspective and opinion sharing, but rather the sharing of personal stories that help enrich each other, much like people have learned from one another for generations through the power of storytelling.

Akira was aware in advance that she’d learn the following:

- Perspective-gathering protocols that her direct reports could implement with their teams

- Communication templates that maintained her values while allowing for personalization

- Structures for different types of feedback loops that ensured diverse voices reached decision-makers

- Recognition systems that reinforced empathetic behaviors across all levels

- How to leverage AI to condense longer-form shares in ways that still allow everyone to feel represented and give summaries for leaders to make informed decisions

Why Stories Change Everything

But here’s the thing: learning those conceptually doesn’t make the impact that we want it to. Empathable was offering the opportunity to learn that through stories.

Abstract concepts about “scaling empathy” don’t stick. But experiencing the challenge through someone else’s real story? That creates the kind of visceral understanding that drives behavioral change. Through immersive scenarios, Akira didn’t just learn about perspective-gathering systems—she experienced what it felt like to be a manager who had to make decisions affecting hundreds of people without adequate input.

This is the difference between intellectual knowledge and embodied wisdom. Data and facts don’t generally change people’s viewpoints, as stories do. Being able to leverage storytelling at scale is a fundamental starting point for how to bridge the empathy gap.

The First Test: From Theory to Practice

When her first major challenge came—rolling out a strategic initiative across her newly expanded team—Akira applied what she’d learned. Instead of attempting impossible one-on-ones with 80 people, she created structured listening sessions and designed feedback systems that ensured every voice could be heard.

Most importantly, she understood how to help those she did have direct access to impart empathy to their own teams. Making managers capable of building and maintaining empathetic cultures happens through an almost train-the-trainer methodology of allowing them to get better at practicing the deeper meaning of empathy that Empathable believes in—which is the ability to acknowledge the meaningfulness of one another’s stories to be as valuable as our own and get better at being curious about each other’s experiences.

The Scaffolding Effect

The cohort-based learning that Akira received during her training is something that she learned how to scale out so that she could create sub-cohorts within the groups she was managing. Each sub-cohort gave each other the opportunity to share experiences and created structured ways that those cohorts could communicate with each other so that they wouldn’t get caught up in opinion sharing or disagreement but actually in the value of each other’s experiences.

The Transformation: When Systems Create Culture

The results surprised everyone. “I’ve never felt so heard by a senior leader I barely know,” one team member commented during an anonymous survey. When a national social justice issue later affected employees, Akira’s systematic approach created what felt like a supportive community despite the organization’s size.

Her team of 80 ended up having higher performance metrics than her original team of 15, and she maintained one of the highest retention rates she’d ever experienced over the next two years. As a testament to the authentic connections her systems fostered, she was recently asked to officiate the wedding of one of her team leads.

The Ripple Effect

What happened to Akira’s team illustrates a fundamental truth: beyond empathy being personalized, when it becomes systemized and operationalized, it scales exponentially. Instead of one leader trying to be empathetic to 80 people, Akira created conditions where 80 people could be empathetic to each other.

This is the difference between empathy as an individual skill and empathy as an organizational capability. The former breaks down under scale; the latter gets stronger with it.

The Blueprint: How Organizations Can Bridge the Empathy Gap

Akira’s success wasn’t accidental—it followed a specific pattern that any organization can replicate:

- Start with Experience, Not Theory Effective empathy training begins with learning how to listen to and share experiences and value those experiences to be as meaningful as your own, then builds frameworks to be able to share one another’s stories in a way that is both respectful but scales out the knowledge that stories contain that concepts often do not.

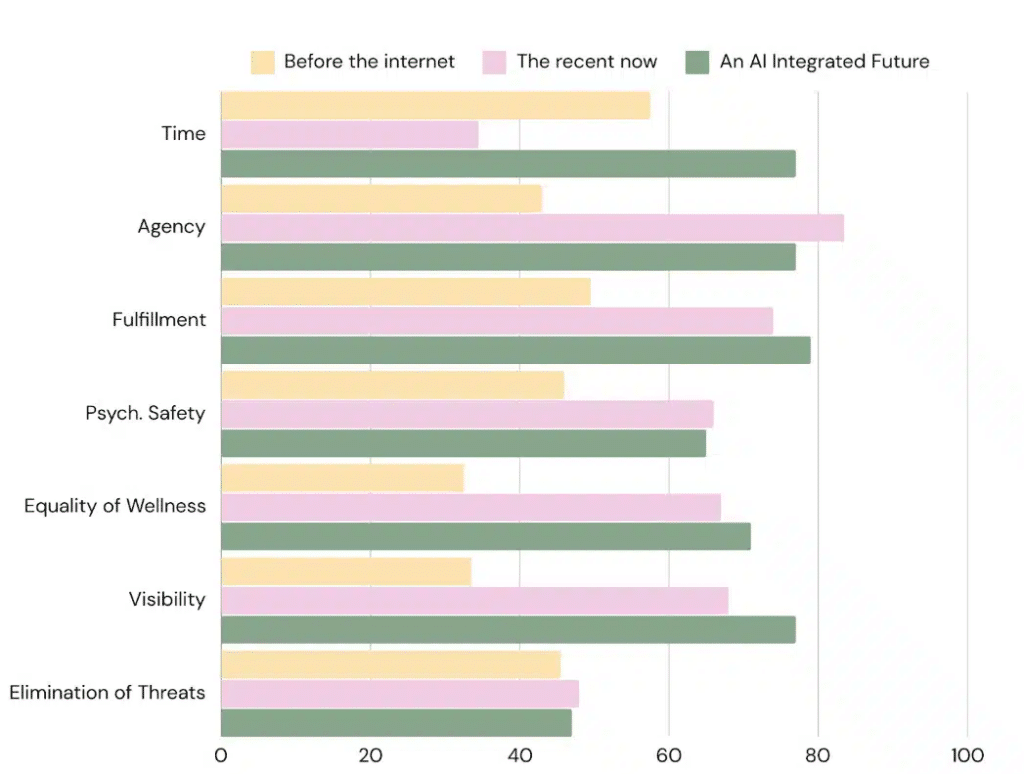

- Focus on Systems, Not Just Skills Don’t just teach managers to be more empathetic; teach them to create empathetic systems. Current perspective-gathering protocols and feedback mechanisms often feel very mechanical and don’t get to the heart of questions that allow people to share in longer form what their actual thoughts and feelings are. Choosing from a scale of one to five can be fine for things like engagement but doesn’t really afford the opportunities that longer-form sharing provides. With AI, survey taking can now accept longer-form thoughts that allow for more informed decision-making.

- Create Scaffolding for Scale The goal isn’t to make every manager capable of personal empathy with hundreds of people—it’s to make every manager capable of building and maintaining empathetic cultures within their sphere of influence through structured storytelling and experience-sharing systems.

- Use Cohort Learning That Scales Akira’s bi-weekly sessions with other managers weren’t just about learning content; they were about processing the challenges of implementing empathetic leadership at scale. This cohort approach can be replicated within organizations, creating networks of support and accountability.

The Future of Empathetic Leadership

The challenge that once kept Akira awake at night became her greatest opportunity for growth—and a model for her organization. What she discovered is that empathy doesn’t diminish when scaled; it transforms from a personal attribute into an organizational superpower.

As organizations continue to grow and become more distributed, the ability to create empathetic systems will become a core competitive advantage. The leaders who master this won’t just manage larger teams more effectively—they’ll create cultures where empathy becomes everyone’s responsibility, not just their own.

The empathy gap isn’t insurmountable. With the right approach, your most caring leaders can become your most effective culture architects. They just need to learn how to build bridges through stories and systems instead of having individual conversations across an ever-widening chasm.

At Empathable, we help organizations develop leaders who can operationalize empathy at scale through immersive, story-based learning experiences. If Akira’s journey resonates with challenges in your organization, we’d love to explore how experiential learning can help bridge your empathy gap. Feel free to schedule time to connect here.